The following is a summary of global temperature conditions in Berkeley Earth’s analysis of June 2023.

- Globally, June 2023 was the warmest June since records began in 1850, and broke the previous record by a large margin.

- In the oceans, June 2023 also set a new record for the warmest June since 1850.

- On land, June 2023 was nominally the 2nd warmest June since 1850, though with an uncertainty margin that leaves it effectively tied with the warmest June (2022).

- Particularly warm conditions occurred in the North Atlantic, Eastern Equatorial Pacific, Canada, the UK, Mexico, southern Africa, and Antarctica.

- Unusually cool conditions were present in the Southwest USA, Western Russia, and Northwest India.

- The North Atlantic reached all-time record warmth by a large margin.

- El Niño was officially declared to have begun in early June, and continues to strengthen.

- 2023 is now likely to become a new record warm year (81% chance).

Global Summary

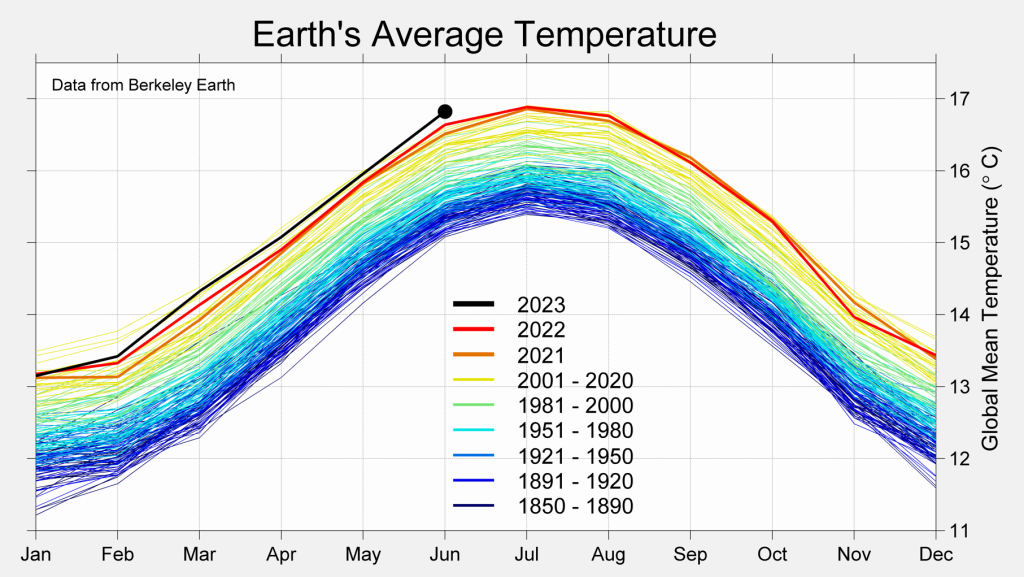

Globally, June 2023 was the warmest June since directly measured instrumental records began in 1850, breaking the record previously set in June 2022. In addition, this June exceeded the previous record by 0.18 °C (0.34 °F), a surprisingly large margin, well outside the margin of uncertainty.

The global mean temperature in June 2023 was 1.47 ± 0.09 °C (2.64 ± 0.16 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average, which is frequently used as a benchmark for the preindustrial period. The global mean temperature anomaly in June 2023 exhibited a significant increase relative to May 2023, rising more than 0.15 °C (0.27 °F).

Though setting a record for June, the temperature anomaly in June was not as large as in March 2023. Because Northern Hemisphere summer months are less variable than Northern winter and early spring months, it is not surprising to see less extreme anomalies during Northern summer.

Temperatures in June were above the long-term trend line, but recent fluctuations remain consistent with natural variability within the ongoing pattern of global warming.

Spatial Variation

June 2023 continues the ongoing pattern of widespread warmth, though with a few exceptions. Particularly warm conditions were present in the North Atlantic, Eastern Equatorial Pacific, Canada, the UK, Mexico, southern Africa, and Antarctica.

Particularly cool conditions were present in the Southwest USA, Western Russia, and Northwest India.

We estimate that 8.3% of the Earth’s surface experienced their locally warmest June average, and 81% of the Earth’s surface was significantly warm when compared to their local average during the period 1951 to 1980. In addition, 0.02% of the Earth’s surface had their locally coldest June.

The Equatorial Pacific in June was strengthening under El Niño conditions. Above average temperatures are present in much of the Pacific, with record warm temperatures for this time of year developing in some areas of the Eastern Equatorial Pacific. An El Niño condition was officially declared by NOAA in early June.

Over land regions, 2023 was nominally the 2nd warmest June ever observed, and warmed modestly relative to May. The land average was 1.81 ± 0.12 °C (3.26 ± 0.22 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average.

The nominally warmest June on land was June 2022. However, June 2022 was only 0.02 °C (0.04 °F) warmer than June 2023. This difference being less than the measurement uncertainty, it is reasonable to describe June 2022 and June 2023 temperatures on land as being effectively tied for first place.

June 2023 was by far the warmest June in the oceans, recorded as 1.12 ± 0.12 °C (2.01 ± 0.20 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average. This beats the previous record for June, which occurred in 2016.

The temperature anomaly for June is also the largest ocean-average temperature anomaly observed in instrumental measurements for any month of the year. This surpasses the previous record of 1.07 °C set in April 2023.

North Atlantic

The North Atlantic Ocean has been record warm in June 2023, beating previous Junes by a large margin, and contributing substantially to the record global average in June. The present anomaly developed rapidly, increasing more than 0.2 °C (0.4 °F) since May, and is highly unusual. Only two previous June averages in the North Atlantic have deviated this far from the long-term trend, and both were in the 19th century.

While global warming has played a role in the long-term rise of North Atlantic temperatures, other factors are at work to explain the sudden high values. One factor is the beginning stages of El Niño. This may have provided some additional warmth to the North Atlantic, though because the El Niño event is only just beginning, this is likely only a small portion of the effect.

Two other factors are also likely to have influenced the development of exceptional warmth in the North Atlantic. The first is the exceptionally low levels of dust coming off the Sahara in recent months. Such dust is a normal occurrence at this time of year, and blocks a small portion of the sunlight. The unusual absence of Saharan dust has allowed for additional heating from the sun. More normal levels of dust have returned in early July.

|  |

The other likely factor is the reduction in man-made sulfur aerosols. In 2020, new international rules governing heavy fuels for marine shipping abruptly reduced sulfur emissions from large ships by ~85%. This change was made to preserve human health, due to the toxic nature of sulfur aerosols. However, such aerosols also reflect sunlight, and as a result have a cooling effect. These sulfur aerosols are believed to have masked some of the effects of global warming, especially in the heavily trafficked North Pacific and North Atlantic regions. An analysis suggests that removing the sulfur aerosols may have added ~0.2 °C (~0.4 °F) to the North Atlantic region. This would not explain all of the present North Atlantic spike, but may have added to its severity.

The reduction in marine sulfur aerosols from shipping, though regionally significant in areas with high shipping volumes, has likely only added a few hundredths of a degree to the global average temperature.

Thus, we believe that record high temperatures in the North Atlantic are likely due to the combination of man-made factors, including global warming and reduced sulfur aerosols, and natural variability, including El Niño and the unusually low Saharan dust.

Antarctica

Another feature of the temperature distribution in June 2023 was unseasonably warm conditions around Antarctica. Though Antarctica remains well-below freezing, and is in the middle of Southern Hemisphere Winter, temperatures in June were not as cold as is typically expected. The sea ice around Antarctica is refreezing far more slowly than in any previously observed year in the satellite record (starting in 1979), running roughly a month behind the typical schedule. This has led to the largest Antarctic sea ice anomaly on record

It is unclear to what extent the unusual evolution of Antarctic sea ice this year may be related to climate change.

El Niño Outlook

June 2023 saw the emergence and strengthening of a new El Niño. An El Niño Advisory — announcing the start of a new El Niño — was officially issued by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center on June 8th. The current CPC/IRI analysis suggests that El Niño conditions will persist for the foreseeable future, at least until next year. Models currently disagree on the likely intensity of the current El Niño, with some models predicting a very strong event, while others are more mild or moderate. The intensifying warm pool in the Pacific will likely give us a clearer idea of what to expect during the next month or two.

El Niño is likely to moderately boost global average temperatures during the rest of 2023 and into 2024. Due to the lag between the development of El Niño and its full impact being felt on global temperatures, it is likely that the current El Niño will have a greater impact on global temperatures in 2024 than it does in 2023.

Year to Date

This year began with a January that was similar to January in 2021 and 2022. However, with the end of La Niña, temperatures diverged markedly in February and March, and are now considerably warmer than in 2021 or 2022. With the development of El Niño and record warmth in the North Atlantic, June warmed significantly relative to May, and is the first month of 2023 to set a new monthly temperature record.

Because there is more land in the Northern Hemisphere, and land temperatures vary more strongly with seasonality than ocean temperatures, the Earth’s global average temperature also peaks during Northern Hemisphere summer. The global average temperature observed in June is warmer than all previous Junes, and only a handful of previous July averages have been warmer.

The most significant spatial features of year-to-date temperatures are the shift towards El Niño, warmth across much of the northern mid-latitudes, cooling in the Western USA, and several ocean hotspots. Year-to-date, 6.6% of the Earth’s surface has experienced average temperatures that are a local record high. In addition, none of the Earth’s surface has been record cold year-to-date.

Rest of 2023

2023 is on pace to be the warmest year yet observed since instrumental measurements began. The surprisingly strong warming in June 2023, combined with the likelihood of a strong El Niño event, have increased the forecast for the rest of 2023. The statistical approach that we use, looking at conditions in recent months, now believes that 2023 is likely to become the warmest year on record (81% chance). This forecast probability is sharply higher than last month’s report, when the likelihood of a record warm year was estimated at 54%. It also represents a large change from the forecast at the beginning of the year (before the development of El Niño), when only a 14% chance of a record 2023 was estimated. If 2023 does not become the warmest year on record, then it would almost surely finish 2nd, 3rd, or 4th.

In this assessment, we also find it nearly certain that 2023 will result in the warmest ocean-average year ever measured (98% likelihood), boosted by global warming and the presence of El Niño. However, it remains unlikely that the land average will set an annual average record in 2023, with a 3rd place finish being the most likely outcome.

Even in the presence of a strong El Niño, the annual average temperature for 2023 would still be unlikely to exceed 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above the preindustrial benchmark.

Because of the lag between the development of an El Niño and its maximum impact on global temperatures, an El Niño that develops during 2023 is likely to have an even larger warming effect on global mean temperature in 2024 than 2023.

Likelihood of final 2023 ranking:

- 1st place (81 %)

- 2nd or 3rd place (15 %)

- 4th place (4 %)

- Top 4 overall (> 99 %)