The following is a summary of global temperature conditions in Berkeley Earth’s analysis of September 2023.

- Globally, September 2023 was the warmest September — and the largest monthly anomaly of any month — since records began in 1850.

- The previous record for warmest September was broken by 0.5 °C (0.9 °F), a staggeringly large margin.

- Both land and ocean individually also set new records for the warmest September.

- The extra warmth added since August occurred primarily in polar regions, especially Antarctica.

- Antarctic sea ice set a new record for lowest seasonal maximum extent.

- Record warmth in 2023 is primarily a combined effect of global warming and a strengthening El Niño, but natural variability and other factors have also contributed.

- Particularly warm conditions occurred in the North Atlantic, Eastern Equatorial Pacific, South America, Central America, Europe, parts of Africa and the Middle East, Japan, and Antarctica.

- 77 countries, mostly in Europe and the tropics, set new monthly average records for September.

- El Niño continues to strengthen and is expected to continue into next year.

- 2023 is now virtually certain to become a new record warm year (>99% chance).

- 2023 is very likely (90% chance) to average more than 1.5 °C above our 1850-1900 baseline.

Global Summary

Globally, September 2023 was the warmest September since directly measured instrumental records began in 1850, breaking the record previously set in September 2020. In addition, this September exceeded the previous record by 0.50 °C (0.90 °F), an enormous margin described by one climate scientist as “absolutely gobsmackingly bananas”.

The global mean temperature in September 2023 was 1.82 ± 0.09 °C (3.28 ± 0.17 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average, a new record for the highest temperature excess of any month.

This is the 14th time in the Berkeley Earth analysis that any individual month has reached at least 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) over the preindustrial benchmark. This also previously occurred in March, July, and August of 2023.

One of the Paris Agreement ambitions has been to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above the preindustrial baseline. That goal is defined in reference to the average climate over many years, so a few individual months or a single year above 1.5 °C do not automatically mean that the target has been exceeded. However, isolated anomalies above 1.5 °C are a sign that the Earth is getting close to that limit. It is likely that global warming will cause the long-term average to exceed 1.5 °C during the 2030s unless significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are achieved soon.

The last four months have been extraordinary in terms of global average temperatures, with new monthly records being set every month and by large margins.

The global mean temperature anomaly in September 2023 exhibited a sharp increase relative to August 2023, rising 0.19 °C (0.33 °F).

The monthly temperature anomaly in September 2023 stands starkly alone as the largest single-month temperature anomaly in the period for which instrumental data exist, since 1850.

Likelihood of the September Record

New records for global mean temperature usually advance by only a small increment over previous records (e.g. 0.1 °C / 0.2 °F). It is unprecedented to see a monthly temperature record being broken by 0.5 °C (0.9 °F), as has just occurred.

Given this, we decided to investigate the occurrence of similar records in a CMIP6 ensemble of climate models. We inspected a collection of 189 model runs from 48 climate models meant to simulate historical and near future global warming. We looked at the margin by which new September temperature records were set in each of the simulated years from 1970 to 2070.

In the collected models, new records usually were set by only small margins, as expected. In fact, we could find only a single example in the models where a new September record was set by more than 0.5 °C (0.9 °F). If the climate models are accurately capturing reality, then such a record is very highly unlikely (roughly 1 chance in 10,000).

Given the apparent unlikeliness of such an event, we should also consider that this abrupt record may be due, in significant part, to factors that the current climate models are not accurately capturing.

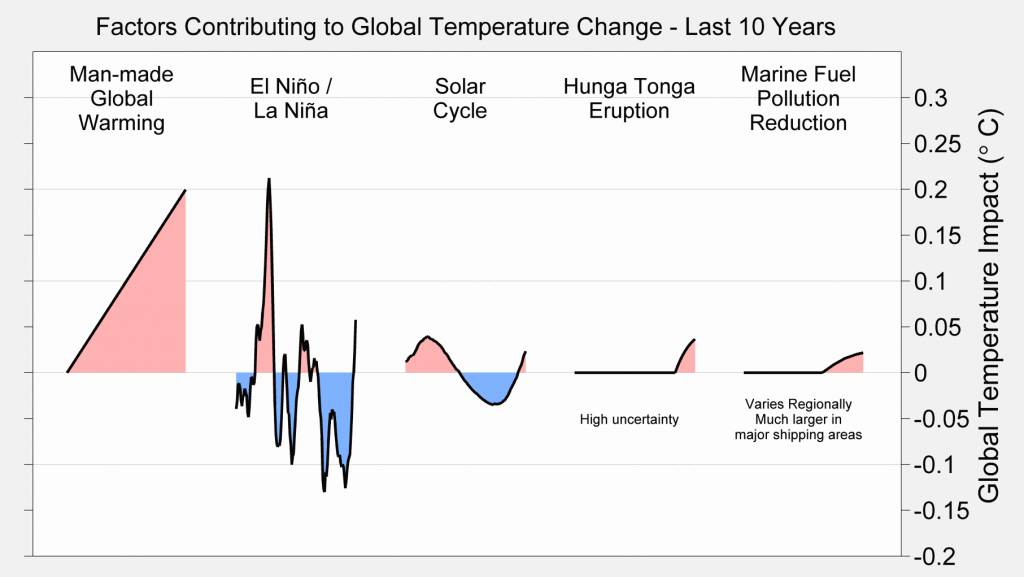

At present, there are some obvious candidates for processes that the models may be failing to fully represent. First, recent reductions in man-made sulfate aerosol pollution have occurred faster and with a different geographic distribution than many models were assuming when they were run. As man-made sulfur aerosols have a cooling effect, their reduction contributes to warming, and may be doing so more rapidly than models expected. Secondly, the very large January 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai was not included in models and may be having unexpected weather effects.

In addition to external factors, it is also possible that models may be generally failing to capture some important aspect(s) of recent year-to-year variability. For example, some models struggle to predict the rate and magnitude of changes in sea ice.

Factors contributing to this unusual extreme are further discussed below.

Spatial Variation

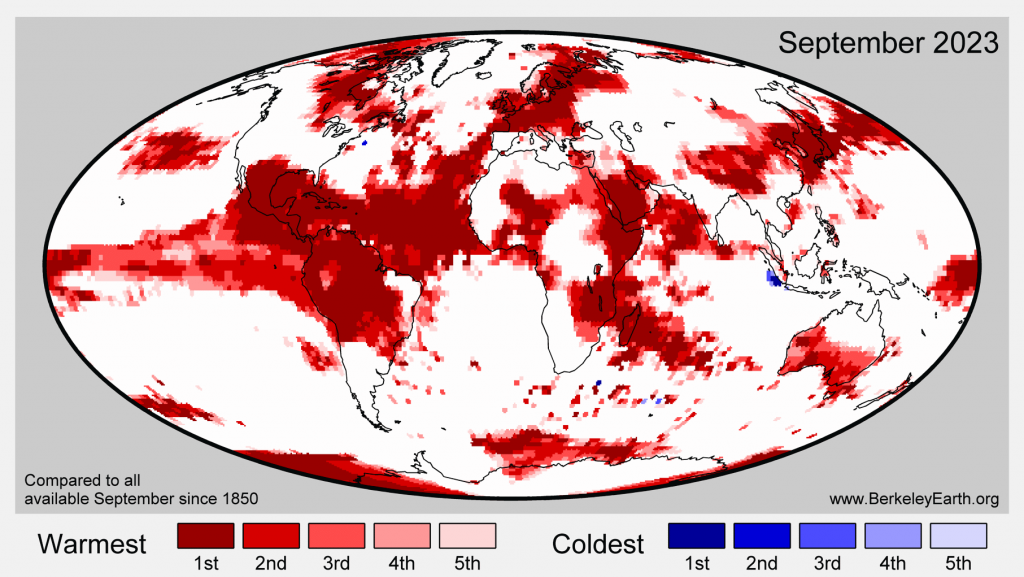

September 2023 continues the ongoing pattern of widespread warmth, with almost no exceptions. Particularly warm conditions were present in the North Atlantic, Eastern Equatorial Pacific, South America, Central America, Europe, parts of Africa and the Middle East, Japan, and Antarctica.

We estimate that 15.7% of the Earth’s surface experienced their locally warmest September average (including 21.7% of land areas), and 87% of the Earth’s surface was significantly warm when compared to their local average during the period 1951 to 1980. In addition, none of the Earth’s surface had their locally coldest September.

The Equatorial Pacific in September is continuing to show strengthening El Niño conditions. An El Niño condition was officially declared by NOAA in early June.

Over land regions, 2023 was also the warmest September ever observed by a large margin, and warmed sharply relative to August. The land average was 2.56 ± 0.15 °C (4.62 ± 0.27 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average. This sharply beats the previous record for September, which was held by 2020.

In total, we estimate that 77 countries (mostly in the tropics and Europe) had their warmest September on record, these were:

Antigua and Barbuda, Austria, Bahrain, Barbados, Belarus, Belgium, Bhutan, Bolivia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Canada, Colombia, Comoros, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czechia, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Germany, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Ireland, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Japan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mexico, Monaco, Mozambique, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, North Korea, Palau, Panama, Peru, Poland, Qatar, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Slovakia, Solomon Islands, Somalia, Somaliland, Suriname, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, The Bahamas, Trinidad and Tobago, United Kingdom, Venezuela, Yemen, Zambia

Note that this list of countries is an estimate based on our gridded temperature analysis and results may differ slightly from what is reported by the local national meteorological agencies.

In addition, some of these broke their September records by extraordinary margins. In Mexico, the September average temperature record was broken by almost 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), a much bigger deviation from trend than ever previously seen.

September 2023 was also the warmest September in the oceans, recorded as 1.21 ± 0.11 °C (2.18 ± 0.20 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average. This beats the previous record for September, which occurred in 2015, by a considerable margin.

The ocean temperature anomaly for September is modestly lower than August and July, but still represents the third warmest monthly ocean temperature anomaly ever measured.

Spatial change since August

While there were some broader reorganizations of weather patterns in September, such as the warming in Europe, the abrupt increase in global mean temperature in September is mostly due to moderate warming in the Arctic and very strong warming in the Antarctic.

When averaged across latitude bands, there was very little change from August to September except in the polar regions, with most of the sharp monthly rise in global mean temperature directly coming from warming around Antarctica. In fact, as noted above, ocean average temperatures cooled slightly in September.

The polar warming last month is in stark contrast to the pattern of warming that has occurred earlier in 2023, which was broadly associated with the transition for La Niña to El Niño and other changes in the tropics and mid-latitudes.

While the stark warming around Antarctica is unquestionably dramatic, it is important to understand that it is not especially unusual. The coldest months in Antarctica are home to some of the most dramatically variable weather on Earth, and such sharp swings towards warmth during September have historically occurred in one year out of every 10-15 years. As large as this change is, the recent swing around Antarctica is nonetheless consistent with natural variability.

While Antarctica is the slowest warming continent in annual average terms, September temperatures in the Antarctic Circle have been trending noticeably higher despite the large year-to-year variability. The current September, though record warm, does not seem inconsistent with past natural variability relative to the long-term trend.

September also contained the annual maximum in Antarctic sea ice. It was by far the lowest maximum for sea ice extent in the modern satellite record (since 1979), and also one of the earliest dates for the peak to be observed. Sea ice extent had already been running at daily record lows for months beforehand.

Low sea ice can contribute to local warming, but local warming can also cause low sea ice. It is not immediately clear to what extent the September warmth in Antarctica was directly caused by the sea ice anomaly vs. to what extent unrelated warming may have been impacting the sea ice. In addition, the excess stratospheric water vapor plume from the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai eruption in January 2022 may have been contributing to both sea ice and temperature anomalies. Further study will be needed to disentangle the multiple possible effects.

Causes of Recent Warmth

As discussed above, the surge in warmth during September was mostly due to warming around the Antarctic circle. However, the record warmth in September was due not only to the recent surge, but also to the extraordinary warmth that had already occurred during the preceding few months.

While the temperature fluctuations around Antarctica during the last month might simply be due to natural variability, the broader changes in 2023 are related to a mix of man-made and natural factors.

Firstly, man-made global warming has been raising the Earth’s temperature by about 0.19 °C/decade (0.34 °F/decade). This is a direct consequence of the accumulation of additional greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, especially carbon dioxide. This is the primary factor responsible for long-term warming.

However, global warming is a gradual process. It does not explain short-term spikes and fluctuations in Earth’s average temperature. The main reason for such spikes is internal variability in the distribution of heat and circulation of the oceans and atmosphere. The largest and most well-known form of short-term internal variability is the El Niño / La Niña cycle originating in the Pacific. During the El Niño phase, global average temperatures tend to be slightly higher. As a result, record highs for global average temperature tend to be set during El Niño years. This year, a new El Niño officially began in June after a multiple year period of La Niña. The rapid transition from a moderately strong La Niña to the current El Niño has played a large role in the warming this year.

The combination of global warming, El Niño, and Antarctic variability are the primary factors responsible for the present high global average temperature. However, other factors may also be playing a minor role. Some of these were discussed in greater detail in last month’s temperature report.

El Niño Outlook

September 2023 saw a further strengthening of the new El Niño that began in June. The current CPC/IRI analysis suggests that El Niño conditions will persist for the foreseeable future, at least until next year. Uncertainty has narrowed, but models continue to disagree on the likely intensity of the current El Niño, with some models predicting a very strong event, while others are more moderate.

El Niño is likely to moderately boost global average temperatures during the rest of 2023 and into 2024. Due to the lag between the development of El Niño and its full impact being felt on global temperatures, it is likely that the current El Niño will have a greater impact on global temperatures in 2024 than it does in 2023. If other factors remain warm, such as the North Atlantic, that raises the possibility that the annual average in 2024 could be even warmer than 2023.

Year to Date

This year began with a January that was similar to January in 2021 and 2022. However, with the end of La Niña, temperatures diverged markedly in February and March, and are now far warmer than in 2021 or 2022. With the development of El Niño, record warmth in the North Atlantic, and now the surge in temperatures around Antarctica, global average temperature in 2023 are running well ahead of any previous year.

June, July, August, and September set new records for monthly average temperature in 2023, and by large and increasing margins. As discussed below, we consider it nearly certain that 2023 will set a new record for the warmest annual average.

The most significant spatial features of year-to-date temperatures are the shift towards El Niño, warmth across much of the northern mid-latitudes, and several ocean hotspots (especially the North Atlantic). Year-to-date, 11.1% of the Earth’s surface has experienced average temperatures that are a local record high. In addition, none of the Earth’s surface has been record cold year-to-date.

Rest of 2023

2023 will almost certainly be the warmest year since instrumental measurements began. The surprisingly strong warming in June through September 2023, combined with the likelihood of a strong El Niño event, have increased the forecast for the rest of 2023. The statistical approach that we use, looking at conditions in recent months, now believes that 2023 is virtually certain to become the warmest year on record (>99% chance).

This forecast probability is essentially unchanged from the last two monthly reports, where we also forecast a 99% chance of an annual record. However, it represents a large change from the forecast at the beginning of the year (before the development of El Niño), when only a 14% chance of a record warm 2023 was estimated.

In this assessment, we also find it nearly certain that 2023 will result in the warmest ocean-average year ever measured (>99% likelihood), boosted by global warming and the presence of El Niño.

However, it remains unclear if the land average will set an annual average record in 2023. Currently, we forecast a 88% chance of a new land-average record in 2023, a significant increase from last month when a land-average record was estimated at 60%.

The surprising recent warmth and the potential for a strong El Niño, has raised our estimates for the final 2023 annual average. We now consider there to be a 90% chance that 2023 has an annual-average temperature anomaly more than 1.5 °C/2.7 °F above the 1850-1900 average. This is a sharp increase from last month’s report, when only a 55% chance of a 1.5 °C anomaly was forecast. Prior to the start of 2023, the likelihood of a 1.5 °C annual average this year was estimated at ~1%. The fact that this forecast has shifted so greatly serves to underscore the extraordinarily progression of the last few months, whose warmth has far exceeded expectations.

Though the IPCC has set a goal to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial, it must be noted that this goal refers to the long-term average temperature. A few months, or a single year, warmer than 1.5 °C does not automatically mean that the goal has been exceeded. However, breaching 1.5 °C this year would serve to emphasize how little time remains to meet this target. Unless sharp reductions in man-made greenhouse gas emissions occur soon, the long-term average is likely to pass 1.5 °C during the 2030s.

Further, we should note that there exist small differences among groups in their assessment of long-term climate change. By a small margin, Berkeley Earth’s estimate of the 1850-1900 reference period is colder than most other groups. As a result, our estimate of the change since the preindustrial period is modestly larger. If 2023 exceeds 1.5 °C this year, it is likely to do so only by a small amount. As a result, these differences between analysis groups are likely to become important. It is entirely possible that some groups will report 2023 as slightly above 1.5 °C while others report it as slightly below. Further discussion of the likely outcomes has been provided by Zeke Hausfather.

Because of the lag between the development of an El Niño and its maximum impact on global temperatures, an El Niño during 2023 may have an even larger warming effect on global mean temperature in 2024 than 2023. It is common for the second year of an El Niño to be warmer than the first year. Whether that ultimately holds true in 2024 may still depend on other factors, such as whether the North Atlantic also remains very warm or settles to a more normal temperature during 2024.