The following is a summary of global temperature conditions in Berkeley Earth’s analysis of June 2024.

- Globally, June 2024 was the warmest June since records began in 1850.

- The previous record for warmest June, set in 2023, was broken by a relatively large margin (0.14 °C / 0.25 °F).

- The ocean-average and land-average each also set new records for the warmest June.

- Particularly warm conditions occurred in South America, parts of Asia, Africa, and large areas of the Atlantic Ocean.

- Parts of Antarctica exhibited unusually cold monthly averages in June.

- We estimate that 63 countries set new national monthly-average records for June.

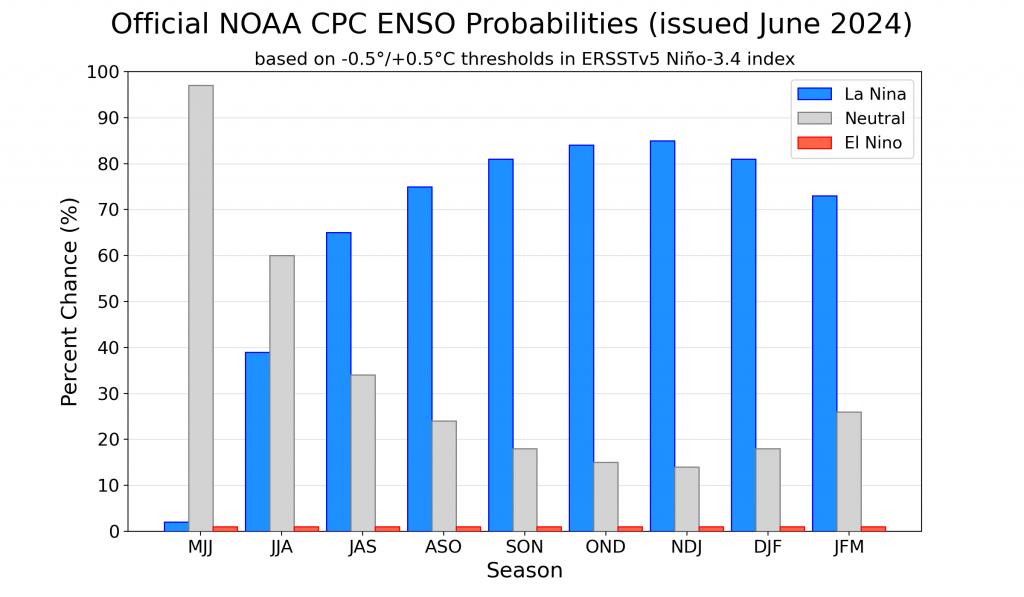

- The El Niño that began last year has now ended. La Niña is expected later this year.

- The 12-month moving-average sets a new record at 1.68 ± 0.07 °C (3.02 ± 0.13 °F) above the 1850-1900 average.

- 2024 is likely to be the warmest year on record.

Global Summary

Globally, June 2024 was the warmest June since directly measured instrumental records began in 1850. It broke the previous record by 0.14 °C (0.25 °F), a relatively large margin clearly outside the range of the uncertainties.

The global mean temperature in June 2024 was 1.60 ± 0.09 °C (2.87 ± 0.17 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average. This is similar to other recent months, though less warm than the peak set last September.

This is the thirteenth consecutive month to set a new monthly record, often by large margins. In addition, June 2024 marks the twelfth consecutive month at least 1.5 °C warmer than the corresponding 1850 to 1900 monthly average.

One of the Paris Agreement ambitions has been to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above the preindustrial baseline. That goal is defined in reference to the average climate over many years, so a few individual months or a single year above 1.5 °C do not automatically mean that the target has been exceeded. However, recent anomalies above 1.5 °C are a sign that the Earth is getting close to that limit. It is likely that global warming will cause the long-term average to exceed 1.5 °C during the early 2030s unless significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are achieved soon.

The global mean temperature anomaly in June 2024 was somewhat warmer than May 2024, though still cooled that January through April.

After 13 consecutive months of record high monthly averages, the 12-month moving average of global mean temperature now stands at 1.68 ± 0.07 °C (3.02 ± 0.13 °F) above the 1850-1900 average. We are likely at or near the peak for this warming event, as relative cooling is expected soon with the end of El Niño. Compared to the long-term trend, the current deviation is one of the largest on record. Other recent large El Niño events, such as 2016 and 1998, produced somewhat smaller deviations above trend. Only the 1878/88 Super El Niño clearly presented a larger deviation above the trend line than the current event.

Spatial Variation

June 2024 continues the ongoing pattern of widespread warmth, with a few important exceptions. Particularly warm conditions were present in parts of Asia, South America, Africa, and large areas of the Atlantic. Parts of Antarctica exhibited unusually cold monthly averages in June.

We estimate that 14.0% of the Earth’s surface experienced their locally warmest June average (including 21.1% of land areas), and 85% of the Earth’s surface was significantly warm when compared to their local average during the period 1951 to 1980. By contrast, none of the Earth’s surface had their locally coldest June.

The El Niño event in the equatorial Pacific has now ended with sea surface temperatures falling below the El Niño threshold. This El Niño was officially declared by NOAA in early June 2023 and lasted about a year. As discussed below, a La Niña is now expected to develop during coming months which will bring with it some relative cooling. The initial phase of this development is visible near South America in the equatorial Pacific.

Over land regions, 2024 was by far the warmest June ever observed. The land average was 2.25 ± 0.15 °C (4.05 ± 0.27 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average. This broke the previous June record, set in 2023, by 0.41 °C (0.74 °F). Such a margin for a new record is highly unusual. This is the largest margin of record ever for a new June land record and eighth largest margin for any monthly land record since 1900.

In total, we estimate that 63 countries, mostly in Africa and South America, had their warmest national-average June on record, these were:

Albania, Algeria, Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Chad, Colombia, Comoros, Cyprus, Djibouti, Dominica, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Federated States of Micronesia, Ghana, Greece, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Israel, Ivory Coast, Jordan, Kenya, Kosovo, Lebanon, Lesotho, Libya, Macedonia, Mali, Mauritania, Montenegro, Nepal, Niger, Northern Cyprus, Paraguay, Republic of Serbia, Romania, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, South Korea, South Sudan, Sudan, Suriname, Syria, Sao Tome and Principe, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Venezuela, and Yemen

In addition, Africa, Asia, and South America each set continent-wide record averages for June.

June 2024 was also the warmest June in the ocean average, recorded as 1.15 ± 0.11 °C (2.07 ± 0.20 °F) above the 1850 to 1900 average. This beats the previous record for June by an small margin, though the current uncertainties are significant.

The ocean temperature anomaly for June is similar to other recent months in 2024, but cooler than in July, August, and September 2023.

According to the European ERA5, daily global ocean average temperatures have now become similar to the records set during the same days of the year in 2023. The oceanic warmth over the last year is due primarily to the combination of El Niño and extremely unusual warmth in the Atlantic. As El Niño has now ended, it is likely that the daily ocean average temperatures will soon slip lower than during 2023 and remain somewhat below 2023 for the rest of the year.

Considered in terms of the average over the last 12 months (July 2023 to June 2024), record warmth has been widespread, especially in the tropics. Large parts of South America, Africa, Southeast Asia, Europe, Canada, and the Atlantic have had a 12-month average that is higher than any previous July to June period. The only region to have significant relative cooling during this period is in Eastern Antarctica.

In total, we estimate that the last 12 months have been the warmest July to June period on record for 138 countries, these were:

Albania, Algeria, Antigua and Barbuda, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Barbados, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Brunei, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Central African Republic, Chad, China, Colombia, Comoros, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czechia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Federated States of Micronesia, France, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Greece, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Liechtenstein, Macedonia, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, North Korea, Oman, Palau, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Republic of Serbia, Republic of the Congo, Romania, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, Slovenia, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Korea, South Sudan, Sudan, Suriname, Switzerland, Syria, Sao Tome and Principe, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Republic of Tanzania, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Vietnam, Western Sahara, Yemen, and Zambia

Causes of Recent Warmth

The record warmth over the last 12 months has been due in large part to the El Niño condition in the Pacific, which is a form of natural variability associated with short-term swings in global temperature. This short-term change occurs alongside a background of longer-term man-made and other natural changes mostly also favoring warming during the present time.

Firstly, man-made global warming has been raising the Earth’s temperature by about 0.19 °C/decade (0.34 °F/decade). This is a direct consequence of the accumulation of additional greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, especially carbon dioxide. This is the primary factor responsible for long-term warming.

However, this global warming is a gradual process. It does not explain short-term spikes and fluctuations in Earth’s average temperature. The main reason for such spikes is internal variability in the distribution of heat and circulation of the oceans and atmosphere. The largest and most well-known form of short-term internal variability is the El Niño / La Niña cycle originating in the Pacific. During the El Niño phase, global average temperatures tend to be somewhat higher. As a result, record highs for global average temperature tend to be set during El Niño years. Last year, a new El Niño officially began in June after a multiple year period of La Niña. The rapid transition from a moderately strong La Niña to the current El Niño played a large role in the warming of 2023.

In addition to the natural El Niño variability, it is likely that other variability also contributed to recent high temperatures. One area of special interest is the Atlantic Ocean. The Northern Atlantic was persistently warm during the second half of 2023 and remains warm in June, with some regions continuing to set records. In recent months, significant warmth has also expanded in the Southern Atlantic. If these changes were entirely natural, the warming spike in the North Atlantic would be rare. However, in previous discussions, we noted that warm anomalies in the Atlantic are likely to be combination of natural variability and man-made regional warming due to new marine shipping regulations that abruptly reduced maritime sulfur aerosol pollution by ~85%.

The current January-June anomaly is the largest deviation from the trend line in several decades. The only comparable anomalies are during the 1878 Super El Niño and during World War II (during which period Atlantic temperatures were quite uncertain due to restricted sampling).

The combination of global warming and El Niño are the primary factors responsible for the recent high global average temperature. However, other factors may also be playing a role. In particular, the evolution of oceanic heatwaves in the Atlantic and other areas is likely to play a large role in determining the outlook for 2024.

El Niño Outlook

June 2024 saw the end of the current El Niño event. The recent El Niño began in mid 2023 and peaked late in 2023 as roughly the 3rd strongest event of the last 30 years. It undoubtedly helped to boost global average temperatures over the last 12 months.

The recent El Niño is likely to moderately boost global average temperatures during 2024. Due to the lag between changes in El Niño condition and its full impact being felt on global temperatures, it is plausible that this El Niño will have a greater impact on global temperatures in 2024 than it did in 2023.

It is now considered likely that a weak to moderate La Niña event will develop late in 2024, this will generate moderately cooler global-average conditions late in 2024. The interplay between the recent El Niño, the possibility of a late 2024 La Niña, and unusual conditions in other regions (e.g. warmth in the Atlantic) will contribute to whether 2024 is or is not ultimately warmer than 2023.

Rest of 2024

With six months completed, 2024 will likely be the warmest year since instrumental measurements began, moderately exceeding the record set in 2023. The first six months of 2024 started with large anomalies, though this is expected to cool somewhat during the latter part of 2024. While beginning with consistent record warmth, whether 2024 becomes the warmest year on record will depend on if it can maintain enough warmth during the next six months to exceed the record annual average set in 2023. However, it is typically true that the second year after an El Niño emerges is warmer than the first, though that is not guaranteed.

The statistical approach that we use, looking at conditions in recent months, now believes that 2024 has a 92% chance of being warmer than 2023, making this outcome likely. The ultimate outcome will depend on the possible switch to La Niña late in 2024, and variation in other regions. However, it is very unlikely that 2024 will be any colder than the second warmest year overall.

Estimated Probability of 2024 Annual Average final rankings:

- 1st – 92%

- 2nd – 8%

- 3rd or lower – <1%

This forecast probability of record warmth is substantially increased from the approximately 50-60% chance previously estimated in January-April.

Individually, we estimate an 97% chance that 2024 has the warmest land-only average measured since 1850. Further, we estimate a 74% chance that 2024 has the warmest ocean-only average. In both cases, the current record was set in 2023.

We also consider there to be a ~99% chance that 2024 will have an annual-average temperature anomaly more than 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above our 1850-1900 average. The annual average in 2023 slightly exceeded the 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) threshold in our dataset, and this is almost certain to occur again in 2024.

Though the IPCC has set a goal to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial, it must be noted that this goal refers to the long-term average temperature. A few months, or a couple years, warmer than 1.5 °C does not automatically mean that the goal has been exceeded. However, breaching 1.5 °C does serve to emphasize how little time remains to meet this target. Unless sharp reductions in man-made greenhouse gas emissions occur soon, the long-term average is likely to pass 1.5 °C during the early 2030s.